PLAY IT AGAIN, CLARE (SIMON AND KEVIN)

Casablanca: The Gin Joint Cut

Perth Theatre

Review by Mark Brown

It is 13 years since Morag Fullarton’s Casablanca: The Gin Joint Cut (the screen-to-stage homage with the dangerously tongue-twisting title) first played to enraptured audiences at Glasgow’s Òran Mór venue. Since then, this hilariously reduced version of Michael Curtiz’s iconic 1942 movie has been performed to full houses in such exciting locations as Paris, London and… Dunoon.

Now Fullarton directs the show – in which three actors play a dozen characters – for Perth Theatre. Martha Steed (who is credited in the programme under the curious title of “design coordinator”) has “coordinated” a smashing set which, in its evocation of the famous Rick’s Café from the movie, is a thing of opulence as compared with the charmingly frugal design offered at the Òran Mór back in 2011.

However, Fullarton knows that much of the humour of the piece depends on its deliberately reduced efforts to evoke the film, whether it is by way of the miniaturised furniture in Rick’s office or a wooden statue standing in for Dooley Wilson’s much-loved pianist Sam.

These elements of design are not the only points of continuity between the original production and this latest staging. Clare Waugh – who played a panoply of characters, including Ilsa Lund (famously, Ingrid Bergman’s role in the movie) and Nazi officer Major Heinrich Strasser, 13 years ago – returns with all the skill, energy and comic timing that fans of the show have come to expect of her.

Back in the day, Waugh was joined by Gavin Mitchell (as Rick Blaine, among others) and Jimmy Chisholm (in numerous roles, including the unprincipled chief of police Captain Renault). Mitchell and Chisholm gave outstanding comic performances. Their unavailability now left two large pairs of theatrical shoes to fill.

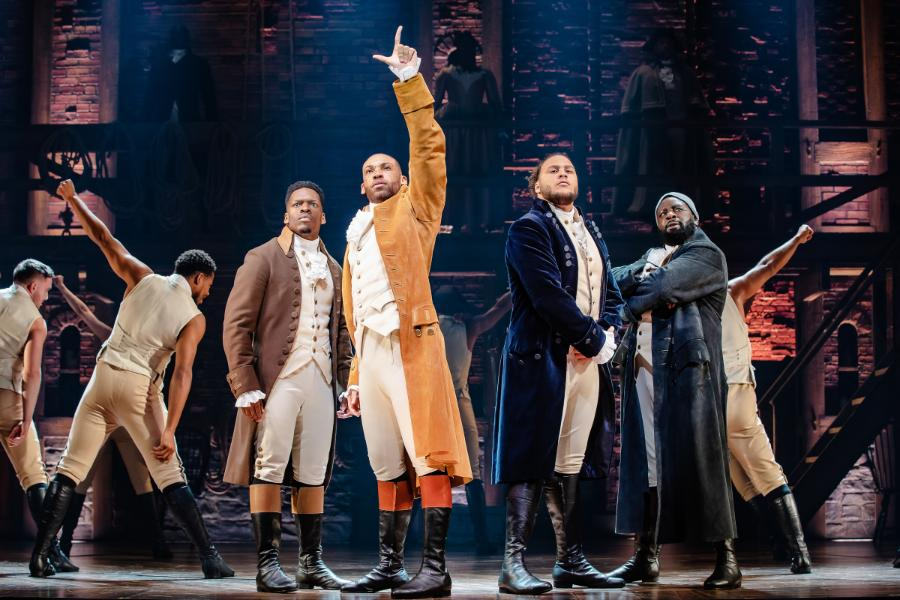

Fullarton has done so brilliantly by bringing in the superb Simon Donaldson (Rick etc.) and the equally fantastic Kevin Lennon (Renault et al). Between them the trio conjure up the kind of comic chemistry that has always been the bedrock of the play’s success.

At the very outset we have metatheatrical introductions to the actors (including Donaldson ironing his trousers while trying out his Humphrey Bogart impressions and Waugh asking anxiously, “where’s my swastika?”). From that moment on the production achieves the perfect balance between fast-paced silliness and comically condensed storytelling.

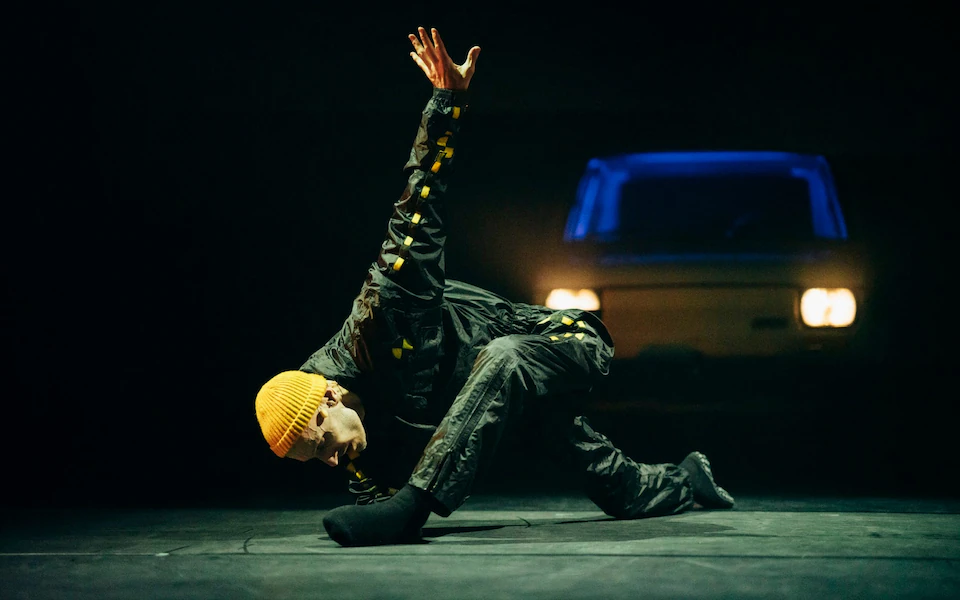

Donaldson swings entertainingly between a respectable impression of Bogart’s playing of the debonair Mr Blaine and delightfully humorous moments of exaggerated mime. Lennon is equally adept, not least in the hilarious scene in which (spinning on his heels while executing costume changes) he plays both Renault and the casually dignified resistance hero Victor Laszlo.

The fabulous singer Jerry Burns sets the tone (and intervenes, stylishly and comically at various points during the show) in the role of the café’s sultry chanteuse. The ever-excellent Hilary Brooks provides piano accompaniment throughout, including during the production’s rousing moment of audience participation, the singing of La Marseillaise.

This is a welcome return, then, for a Scottish theatrical gem. Thank goodness they’re playing it again.

Until March 30: perththeatreandconcerthall.com

This review was originally published in the Sunday National on March 24, 2024

© Mark Brown